The Sandpit | Brian Lewis

Posted: March 31, 2014 Filed under: Brian Lewis 1 CommentI am sitting in a pit in the back yard of my parents’ house. I am playing with a spade and a bucket and a few inches of sand. I am six years old. As I look up from the pit I see the house that my father has made. My father is a builder. I look down at the pit. It is not really a pit, the sides do not reach my ankles, the base is level with the concrete yard. When I push the spade down it buckles instantly. My father is a builder. He has filled the pit with builders’ sand. If I stand up the pit will disappear. I know this isn’t a beach. We are many miles inland. Yet I have built a shore from a memory of the shore. There is only room for me here.

We attain to dwelling, so it seems, only by means of building. The latter, building, has the former, dwelling, as its goal. Still, not every building is a dwelling. Bridges and hangars, stadiums and power stations are buildings but not dwellings; railway stations and highways, dams and market halls are built, but they are not dwelling places […] These buildings house man. He inhabits them and yet does not dwell in them, when to dwell means merely that we take shelter in them.

Building Dwelling Thinking, Martin Heidegger

It seems that an uncoupling of ‘dwelling’ from ‘building’ has taken place, and that something intrinsic to ‘dwelling’ has been diminished or lost. Heidegger’s ontological engagement with ‘dwelling’ and ‘building’ (a recurring theme of his later work) and his consideration of the etymological root shared by the two words – the Old English and Old High German word buan means ‘to dwell’ and also ‘to build’ – leads him to argue for their reconciliation. Dwelling is not merely the end of building, according to Heidegger; it is the condition from which building proceeds, and can only proceed. We do not dwell because we have built, but we build and have built because we dwell. Yet building, in turn, makes dwelling possible; it produces the locations that shelter our lives and ‘gives form’ to dwelling. Heidegger concludes his essay with a detailed description of a farmhouse on the edge of the Black Forest, a farmhouse ‘built some two hundred years ago by the dwelling of peasants’. Its presence – which is to say its permanence – is achieved in ‘a distinctive letting-dwell’, the roof shielding its chambers against storms and snows, the chambers allowing for the ‘hallowed places’ of childbed and coffin.

It was in this farmhouse – a small, three-roomed cabin – that Heidegger wrote Building Dwelling Thinking in the summer of 1951. Adopted as his occasional residence in 1922, its rootedness and seclusion enabled and sustained the development of his thought for nearly fifty years. That Heidegger referred to it as ‘the hut’ is indicative of both its intimacy and its status as a refuge, its remoteness from the engineered and networked century signified by a lack of running water (and, for some years, electricity).

It was in this farmhouse – a small, three-roomed cabin – that Heidegger wrote Building Dwelling Thinking in the summer of 1951. Adopted as his occasional residence in 1922, its rootedness and seclusion enabled and sustained the development of his thought for nearly fifty years. That Heidegger referred to it as ‘the hut’ is indicative of both its intimacy and its status as a refuge, its remoteness from the engineered and networked century signified by a lack of running water (and, for some years, electricity).

Although it resists an engagement with (or concessions to) modernity, ‘the hut’ is, however, distanced from its humble origins by its terms of use. While it still resembles a peasant farmhouse, it now serves time – for part of the year – as a writer’s retreat. The viability of this place of voluntary exile is secured by its owner’s employment in the city, where he also has his main place of residence. The hut owes its continued authenticity, its ‘letting-dwell’, to the contemporary forces that would appear to imperil this authenticity.

Perhaps all retreats are indebted to their respective ‘elsewheres’. A retreat, in the spiritual or recreational sense, implies a leave-taking, a journey, and an eventual return (to ‘normative’ social structures). Also implicit in the idea of the retreat is the promise of a simpler mode of being, enacted in a simple, stable site: a lodge, a cabin, a hut. For most of us, places of retreat are usually found closer to home, and are often located in the house or its grounds; the shed, the study, the prayer room. These sites – commonly, but not exclusively, designed and used by adult males – embed the idea and practice of the retreat within the house itself: microhabitats that enable a more intimate and ‘authentic’ being-in-the-world partly through (intentionally) limiting the physical parameters of that world. For many children, a place of retreat is often found elsewhere in the neighborhood, and is frequently defined by a supposed lack of visibility within (or authorization by) the ‘adult world’: secret spaces (marked out in woods, on waste ground and on common ground), sometimes only physically accessible to small children (via gaps in hedges and fences), open to exploration and risk. Unlike the adult ‘dens’, these sites are contingent and difficult to secure, and are liable to be disturbed or destroyed by weather, animals, adults, or other children.

Both the adult’s and the child’s ‘retreat’ offer a space (additional to and distinct from the ‘normative’ social space) in which we might experience an enlargement or development of our ideas of ‘being’. That this enlargement is enacted in a microhabitat is not the paradox that it might, at first, appear to be; for the experience of the microhabitat is always qualified by an awareness that the house and its resources, distantly (or not-so-distantly) underwriting the microhabitat, can be recalled without difficulty. Very few of us are reconciled to an existence in which the microhabitat is our only habitat. What of those of us who are?

In Building Dwelling Thinking, Heidegger surveys the structures that ‘are buildings, but not dwellings’: ‘bridges and hangars, stadiums and power stations’, to name but a few. How might we begin to speak of ‘dwellings’ that are not buildings?

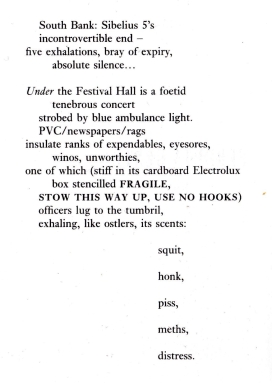

In his collection Perduta Gente, the poet Peter Reading focuses on the fates of the ‘expendable’ homeless in late 1980s Britain, a people abandoned to makeshift and exigent shelters, paper-thin half-worlds on the edges of the built environment, cardboard cities beneath the concrete, glass and steel of central London. The book opens with a double vision of the Royal Festival Hall: the concert hall itself, in which we hear the last chords of Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony, and the hall’s undercroft, where some of the 50,000 homeless people estimated to be living in the area have settled, and which now offers up its own ‘last movement’.

In his collection Perduta Gente, the poet Peter Reading focuses on the fates of the ‘expendable’ homeless in late 1980s Britain, a people abandoned to makeshift and exigent shelters, paper-thin half-worlds on the edges of the built environment, cardboard cities beneath the concrete, glass and steel of central London. The book opens with a double vision of the Royal Festival Hall: the concert hall itself, in which we hear the last chords of Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony, and the hall’s undercroft, where some of the 50,000 homeless people estimated to be living in the area have settled, and which now offers up its own ‘last movement’.

Cardboard and newspaper are the materials from which many of these dwellings are improvised, in pointed contrast to the planned and built spaces above and around them. Newspapers also supply Reading with a number of the ‘found texts’ that appear throughout Perduta Gente, an unstable arrangement of letters, diary entries, scribbled notes, official documents and advertisements for luxury penthouses and derelict barns (the latter briefly occupied by one of the book’s protagonists). Within this patchwork of papers are fragments of ‘secret documents’ pertaining to radioactive leaks (the documents are apparently genuine, and were procured and reproduced illegally), seemingly passed to the author by a former nuclear physicist who, after being exposed to ‘a radio dose’, finds himself unemployable and living in a squat. The theme of nuclear contamination becomes more pronounced and more closely intertwined with the theme of homelessness through the book’s fragmentary collages. Writing in the aftermath of the Chernobyl disaster of 1987, Reading uses the example of an endangered microhabitat – the disquieting but all-too-commonplace predicament of the destitute – to illustrate the even greater imperilment of European habitats by environmental catastrophe.

Similarly, the continual shifts between the ‘macro’ and the ‘micro’ heighten our sense of individual lives – and habitats – under acute pressure. The mode is one of steady, unrelenting reduction of the circumstances in – and of the materials from – which these fragile microhabitats are salvaged. The ‘derries’ (derelict houses), squats, sties and barns are either demolished or redeveloped and resold, their unauthorized occupants evicted. The ‘lone hag gippo’ whom we encounter in a (progressively degraded) caravan at the start of the book ends her days in a cardboard box, ‘etiolated and crushed’. The homeless are forced into smaller and smaller spaces, the shrinking surplus of the built environment (as more space is seized by developers), and are obliged to furnish these spaces with the discards of the consumer environment. Refuges are assembled from refuse, only to be reclaimed as refuse, sometimes with the deceased occupants inside. The homeless fare no better on the coast: their flimsy shelters, ‘wedged in the clefts of the dunes’, are discovered by the wardens of a nature reserve. The Gente perduta return from their beachcombing to find ‘a yellow and black JCB / scrunch[ing] shacks into a skip.’

The Isle of Sheppey lies just off the north coast of Kent, some 46 miles east of London. It is a Saturday evening in July 2003 and I have been walking for 12 hours, tracing the course of Milton Creek near Sittingbourne to the point, a few miles north-east, where its silt and flow merges with that of the Swale, a thin, grey channel dividing Sheppey from the mainland, forded by a low vertical-lift bridge carrying road, rail and pedestrian traffic. On crossing the Swale, I sink between the island’s first lines of defence: a ridge of baked earth and a flooded ditch, the lines parting south of Queenborough, its marina flanked by spreading works, a river wall hardening into a sea wall that runs north to Sheerness port, concrete raised against the tidal Thames and the North Sea. As the land slumps east, so does the sea wall, until the cliffs of Warden assert their own protection; below the sea wall, the island’s remaining pill-boxes, tide-lapped, listing, losing ground.

The Isle of Sheppey lies just off the north coast of Kent, some 46 miles east of London. It is a Saturday evening in July 2003 and I have been walking for 12 hours, tracing the course of Milton Creek near Sittingbourne to the point, a few miles north-east, where its silt and flow merges with that of the Swale, a thin, grey channel dividing Sheppey from the mainland, forded by a low vertical-lift bridge carrying road, rail and pedestrian traffic. On crossing the Swale, I sink between the island’s first lines of defence: a ridge of baked earth and a flooded ditch, the lines parting south of Queenborough, its marina flanked by spreading works, a river wall hardening into a sea wall that runs north to Sheerness port, concrete raised against the tidal Thames and the North Sea. As the land slumps east, so does the sea wall, until the cliffs of Warden assert their own protection; below the sea wall, the island’s remaining pill-boxes, tide-lapped, listing, losing ground.

I am somewhere between the towns of Minster and Warden and I have nowhere to rest, the light having less than an hour left in it. If I turn south I am likely to find myself on the road to Eastchurch, beyond which lie the island’s three prisons, rising just above the creeks, fleets and marshes that wind into a nature reserve, before falling back into the Swale. If I continue east along the coastal path it will be caravan parks, shrunken lets, empty but defended. I descend from the path to the shoreline, daylight silvering to moonlight, cliff-edges bulking to my right. After an hour or so, I notice an opening in the cliffs and start to push inland. As I approach it, the opening falls into cliff-shadow; I am unsure of my footing, and I turn back to the shore.

I turn back to the shore, taking two or three wrong turns in the dark, slowly piecing together the outline of a small structure built into the foot of the cliff. I walk towards it and see that it is a shelter, timbered roof, two sides panelled, two sides open to the coast. I step inside it, stooping slightly, and rest on the low, narrow bench that runs around the panelled sides. There is room for perhaps two adults, or four small children. There is no litter. The space is clean and well-constructed; there is not enough light to show me how old it is. As I settle into the shelter it seems to take possession of the coast. Perhaps it belongs to a family in one of the detached houses set back from the cliff. It has nothing of the town in it apart from a large white rubble bag folded under the bench. The rubble bag is empty but for a few specks of aggregate. I climb into it but it is the wrong shape and so I climb out again. I look down at the sand floor of the shelter. It is the sandpit left over from my childhood, rebuilt to fill someone else’s childhood, and no longer fitting the space I have made for it.

An earlier version of The Sandpit (‘Camping without Tents’) was among the papers presented at the Occursus symposium on Microhabitats at Bradley’s Cafe, Sheffield, Fri 28 March 2014 (click here for the full programme). The full text of Martin Heidegger’s Building Dwelling Thinking (tr. Alfred Hofstadter) appears here. A recording of the full text of Peter Reading’s Perduta Gente (made by Reading for the Lannan Foundation in 2002) is available as a free audio podcast here.

Heidegger, Martin. 1951. ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’ (in Poetry, Language, Thought). Tr. Hofstadter, Alfred. 1971. New York: Harper Colophon.

Reading, Peter. 1989. Perduta Gente. London: Secker & Warburg.

An exquisite weaving of symmetries.