The Marketplace | Brian Lewis

Posted: December 31, 2016 Filed under: Brian Lewis 1 CommentThe city-states of ancient Greece had a name for their artistic, political and spiritual centre: the agora, an open, expansive ‘gathering place’, in which the polis would assemble for military duty and listen to consular speeches. Over time, the political function of the agora was moderated by its use as a marketplace, with merchants setting up their stalls between colonnades. The later Greek verbs agorázō (“I shop”) and agoreúō (“I speak in public”) reflect the dual life of the agora as a commercial and civic space, and, perhaps, embody an idea (or ideal) of interdependency. It’s an idea that I’d like to explore, and affirm, while also paying tribute to some of the people and collectives whose inspiration and support has been invaluable to me (and to Longbarrow Press) this year. In England (if not the UK), the cultural and political narrative is, all too frequently, one of mute, impersonal, frictionless transactions; disconnection, dispossession, division; a retreat into echo chambers and virtual exclaves. There’s a case to be made for this, of course, and for the claims that our public discourse has been cheapened, that our civic spaces have been eroded. It’s not the only story, though.

Longbarrow Press was founded in 2006, and was initially funded with some of the income from my job as a financial services administrator. When I left the security of a full-time (albeit poorly-remunerated) employed position in 2012, to relocate from Swindon to Sheffield and to give my full attention to Longbarrow’s development, I’d barely addressed the question of the press’s economic survival (or my own). My savings wouldn’t last forever, and the prospect of working entirely from home, with little of the routine association with which I’d become familiar in an open-plan office, was faintly alarming. Slowly, I began to make contact with people in my new surroundings, and further afield, picking up bits and pieces of freelance work. Among the first of these projects was Place & Memory, a creative professional development programme devised and mentored by Judit Bodor, Emma Bolland and Tom Rodgers (aka Gordian Projects), taking eight Leeds-based artists into the city for sessions of collective site research, documented through a range of media (photography, film, audio, drawing, found objects, poetry and prose. Some of this material appears in a book). I was recruited as a sound recordist for the project, and found myself spending more and more time at Inkwell Arts in Chapel Allerton, north Leeds, where the group was headquartered. Inkwell is a community-focused arts space, cafe and studio complex on the site of a former pub, renovated and adapted over several years, offering structured support for creative individuals as part of their recovery from mental health issues. The cafe and gallery is the hub, a bright, open, accessible room, enabling conversation between friends and strangers, planned and unplanned encounters. After the project drew to a close in summer 2014, I found that I missed the artists, the staff, the space. Fortunately, I was invited back at the start of this year, working with a new intake of artists to develop websites showcasing their creative CVs and works-in-progress. Most of the sessions were 1-1 tutorials, with space for discussion, application, and growth, the focus and pace varying from one hour to the next. Invariably, I’d be asked at least one question to which I didn’t have an immediate answer, and we’d work out a solution together. There was a sense of shared discovery in each of these encounters: listening, looking, learning. The mentoring programme spanned three months, time enough to rethink my ideas about dialogue, project development and workspace.

A week or so after leaving Inkwell, I returned to Leeds for the opening of Shoddy, a group exhibition organised and curated by disability rights activist Gill Crawshaw. The exhibition was both a collective exploration of reused textiles (alluding to the original meaning of ‘shoddy’: new cloth made from woollen waste, a process patented in West Yorkshire) and a creative challenge (or rebuke) to the government’s ‘shoddy’ treatment of disabled people. Fittingly, the venue was the former premises of an Italian clothing wholesaler, now ‘repurposed’ by Live Art Bistro, a Leeds-based, artist-led organisation. The preview was packed, and, unlike some that I’ve attended, the work on display was central, not peripheral, to the occasion. And it was fresh, the thinking and the making, shaped from recycled materials, installed in a secondhand space. Felt. Cloth. Polythene. Paper. Yarn. Natalia Sauvignon’s ‘Beautiful but Deadly’, a sculpture utilising woollen remnants, plastic plants, seashells from the east coast, human hair. ‘Shoddy Samplers’, a duo of embroidered textiles by Faye Waple, juxtaposing the early and later usages of ‘shoddy’ (as noun and adjective). A collaborative, multi-sensory wall hanging by Pyramid of Arts, incorporating marks, stitches and woven parts from each of its members. All the leftovers from the marketplace, the scraps and offcuts, gifts passing from hand to hand. A few months after the first Shoddy exhibition, Gill hatched another, to be held at Inkwell in August. She had a small budget for a print publication, drawing on texts and photographs from the first show, and asked me if I’d be interested in taking on the design and editing work. I said yes, and we met to discuss the brochure spec. We agreed that the Shoddy booklet should aim to meet the accessibility criteria of the exhibitions. Translated into print, this meant taking care to ensure that the page layouts were interesting, without presenting obstacles for readers with visual or cognitive impairments. We settled on Futura, a clean, modern sans serif typeface, for the headline and body text (the latter in 12pt throughout); paragraphs flush left; black body text with blue titling; wide margins; minimal italicisation. Although I’d spent several years refining my approach to design with many of these questions in mind, it was the first time I’d asked them in the interests of something other than my own aesthetic. A printed page, like a public place, should invite us in, without clutter or impediment; once inside, it should enable us to navigate, to apprehend each part and to make connections, to read the space between columns. Gill, assisted by volunteers at Inkwell, arranged the Shoddy display with good sightlines, texts and labels at a height accessible to wheelchair users, and a clear, inventive visual narrative from wall to wall. As with the first show, it developed from a sense of community, affirmed and renewed by the audience at the opening night at Inkwell, and in the days that followed. People gathering, talking, drinking coffee, tea, taking in the work.

A week or so after leaving Inkwell, I returned to Leeds for the opening of Shoddy, a group exhibition organised and curated by disability rights activist Gill Crawshaw. The exhibition was both a collective exploration of reused textiles (alluding to the original meaning of ‘shoddy’: new cloth made from woollen waste, a process patented in West Yorkshire) and a creative challenge (or rebuke) to the government’s ‘shoddy’ treatment of disabled people. Fittingly, the venue was the former premises of an Italian clothing wholesaler, now ‘repurposed’ by Live Art Bistro, a Leeds-based, artist-led organisation. The preview was packed, and, unlike some that I’ve attended, the work on display was central, not peripheral, to the occasion. And it was fresh, the thinking and the making, shaped from recycled materials, installed in a secondhand space. Felt. Cloth. Polythene. Paper. Yarn. Natalia Sauvignon’s ‘Beautiful but Deadly’, a sculpture utilising woollen remnants, plastic plants, seashells from the east coast, human hair. ‘Shoddy Samplers’, a duo of embroidered textiles by Faye Waple, juxtaposing the early and later usages of ‘shoddy’ (as noun and adjective). A collaborative, multi-sensory wall hanging by Pyramid of Arts, incorporating marks, stitches and woven parts from each of its members. All the leftovers from the marketplace, the scraps and offcuts, gifts passing from hand to hand. A few months after the first Shoddy exhibition, Gill hatched another, to be held at Inkwell in August. She had a small budget for a print publication, drawing on texts and photographs from the first show, and asked me if I’d be interested in taking on the design and editing work. I said yes, and we met to discuss the brochure spec. We agreed that the Shoddy booklet should aim to meet the accessibility criteria of the exhibitions. Translated into print, this meant taking care to ensure that the page layouts were interesting, without presenting obstacles for readers with visual or cognitive impairments. We settled on Futura, a clean, modern sans serif typeface, for the headline and body text (the latter in 12pt throughout); paragraphs flush left; black body text with blue titling; wide margins; minimal italicisation. Although I’d spent several years refining my approach to design with many of these questions in mind, it was the first time I’d asked them in the interests of something other than my own aesthetic. A printed page, like a public place, should invite us in, without clutter or impediment; once inside, it should enable us to navigate, to apprehend each part and to make connections, to read the space between columns. Gill, assisted by volunteers at Inkwell, arranged the Shoddy display with good sightlines, texts and labels at a height accessible to wheelchair users, and a clear, inventive visual narrative from wall to wall. As with the first show, it developed from a sense of community, affirmed and renewed by the audience at the opening night at Inkwell, and in the days that followed. People gathering, talking, drinking coffee, tea, taking in the work.

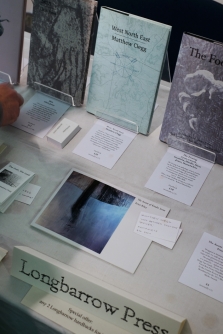

I picked up the Shoddy assignment the day after Hillsfest, an ambitious arts weekender for North Sheffield, conceived and directed by Karen Sherwood (founder of Sheffield’s Cupola Gallery) and staged in my own community of Hillsborough. I’ve reflected on my part in the festival (as curator and MC of the spoken word programme) in an earlier blog post, but I’d like to restate my appreciation for Karen, and acknowledge the extent to which her ethos (as a gallery owner, arts entrepreneur and community organiser) has influenced my own. Sheffield is, by common consent, a welcoming city; Cupola has always been among its most welcoming spaces. Visitors are greeted with free coffee (and, if they’re new to the gallery, a brief tour) and immediately put at ease. The work on display is as varied, challenging and thoughtfully presented as you’ll find in any contemporary art space, and it’s framed by warmth, not cool detachment. Karen, it must be said, is a resourceful, effective salesperson (a key factor in the survival and growth of Cupola over the last 25 years), but she has no appetite for persuading customers to buy things that they don’t need. People trust her judgment, and, in turn, learn to trust their own. At first, I wasn’t convinced that I had all the skills required for the Hillsfest role, but Karen believed that I was equal to the task, so I came to believe this too. It helped that the festival team felt like a small community, working for the benefit of a larger community, one nested inside the other. It’s important to me and, I think, to others, that these principles of openness and interdependency should be to the fore in every Longbarrow event, shared within the collective and with the audience. Our long-running series of poetry walks (the most recent of which took place in the Rivelin Valley a few months ago, led by Karl Hurst and Fay Musselwhite) is, among other things, a space for conversation, conviviality, companionship. The landscape invites us to listen, to catch fragments of observational detail, musings on ecology and history, anecdote and conjecture. We all learn, even (or especially) those of us who have been walking these paths for years, we all gain. I don’t think of ‘the local’ as something to be fetishised, monetised, or, for that matter, disparaged. I don’t understand the recent use of ‘community’ as a pejorative term, a prefix that limits or weakens a project or initiative. It tells me that there’s something at stake. A few months ago, I took part in the Small Publishers Fair at London’s Conway Hall, organised by Helen Mitchell. It was the second year that Longbarrow Press had taken a stall at SPF (sharing, once again, with Gordian Projects); as in 2015, I was struck by the sense of common endeavour, mutual interest and support that prevailed throughout (which some might find unusual in what is, ostensibly, a marketplace). We might attribute this to several factors (none of them predominant): the character of the artists and publishers, selected by Helen; her calm, friendly, positive influence, sincere engagement and focused direction; the volunteer teams; the audiences, some of whom I’d encountered at previous events, who brought their conversations to our tables, and made the exchanges reciprocal, not transactional; and the Conway Hall itself, built in 1929 by nonconformists (the Conway Hall Ethical Society now advocates secular humanism), and still an important gathering place for political and cultural events. It was Helen who made me aware of the hall’s history as a meeting place for collective walks; the society’s members would congregate at 25 Red Lion Square, then set out for Bloomsbury and Clerkenwell. In the heart of the city, yet altogether local. A community in itself, and a place for communities to gather, from near and far.

It was the spirit of the Small Publishers Fair that had called me back for a second year, and which I now sought to muster in Sheffield. On the last Saturday of November, I presented an Independent Publishers Book Fair at Bank Street Arts, in the city’s Cathedral Quarter, with the support of Tom and Andrew at BSA and Emma Bolland (who was also staffing the Gordian Projects stall at the fair, and curating a programme of talks, readings and projections in the evening). I’d participated in two previous book fairs at Bank Street Arts, and wondered if a one-day event, along similar lines, might be viable; Tom and Andrew were immediately receptive to the idea, and put their creative and technical resources at our disposal. The opportunity to invite presses whose work I admired was a privilege; happily, almost everyone I contacted was able to take part. The line-up comprised mostly Sheffield-based (or Sheffield-affiliated) publishers and artists – And Other Stories, enjoy your homes, Gordian Projects, Joanne Lee, Longbarrow Press, The Poetry Business, Tilted Axis Press, West House Books – with others from further afield: Bradical (Bradford), Comma Press (Manchester), Jean McEwan (West Yorkshire), Peepal Tree Press (Leeds). This was the balance I’d hoped we might achieve: artists’ books, poetry, fiction, art writing, literary criticism, zines; a showcase for some of the work being published in Sheffield, while making (or renewing) connections with fellow practitioners in the north of England. As well as being a one-day ‘marketplace’, I wanted the fair to offer an opportunity for creative exchanges, unhurried conversations, surprise and reciprocity. I knew that everyone I’d invited would have something to contribute, and I was especially pleased that Jean McEwan and Bradical (who shared a table on the day) were able to take part. Jean is a collage artist, a maker of zines and ‘altered postcards’, and founder of Wur Bradford, an art and social space in a stall in Kirkgate Market, central Bradford. The stall hosts printmaking and zine-making workshops, art parties, community dialogues, informal education sessions, artists’ talks, and more. Bradical (who I first met at a Wur Bradford event) have been an important part of this development, challenging Islamophobia and stereotyping through pointed and playful zines and actions, and sharing Jean’s DIY ethic and strategies for engagement. Jean has invited me to speak at a couple of Wur Bradford events in the past few years, and I’m always humbled and inspired by the creativity, generosity, and energy in the room. On Saturday 26 November, these forces were at work at Bank Street Arts, in the dialogues and discoveries, the acts of friendship and solidarity. Jean said something about the inherent value of being in a room with people, of simply talking with them, and I remembered something else that she’d said, that validation was nothing to do with status, or sales, that it is something that happens in the act of exchange. I thought of my mother, now in her late 70s, staffing the Lawn Community Centre Christmas Bazaar that same day, in Swindon, many miles south. The community centre was a group sketch in the 1970s, and was eventually realised in 1999, on the site of an extinct pub. The intervening decades were spent fundraising, campaigning, organising, and challenging indifferent councillors (who maintained that the project was futile, then declared it a success shortly after it opened). Through it all, the community association kept their nerve, their humour, their belief. I watched them, a child of the estate, helping out with jumble sales and recycling drives, I saw what they could do, working together, supporting each other.

Finally, I’d like to thank someone whose support and creative stimulus has been invaluable throughout 2016, as it has been for several years; the artist and writer Emma Bolland, without whom many of the people, places and projects mentioned in this piece would almost certainly be unknown to me. There is no debt, only reciprocity, and work continuing.

Brian Lewis is the editor and publisher of Longbarrow Press. He tweets (as The Halt) here. The second edition of East Wind, a pamphlet comprising three prose sequences and one haiku sequence, is available now from Gordian Projects; click here for further details.

Reblogged this on Shoddy exhibition and commented:

Brian Lewis of Longbarrow press looks back on some of his projects and collaborations of 2016 in terms of the idea of “the marketplace” where sharing, gifting and working together takes place.

It was a pleasure to work with Brian on the Shoddy publication, which turned out wonderfully: an attractive design that was clear and uncluttered.

It’s interesting to read Brian’s take on both the publication and the exhibition in this post from the Longbarrow blog.